Protecting land and livelihoods in Bangladesh's river deltas

Project overview

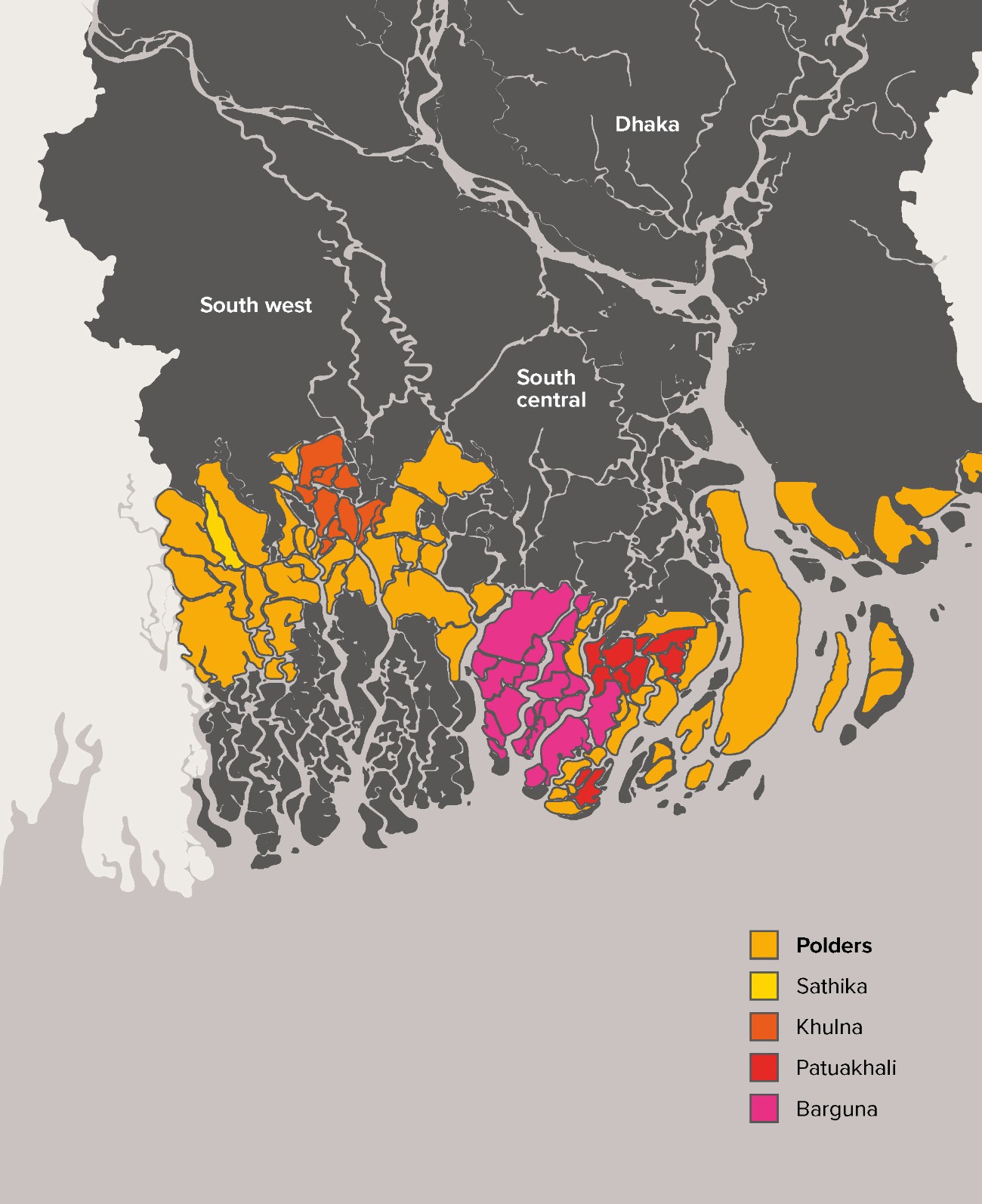

Blue Gold has improved people’s security and prosperity across 22 of Bangladesh’s approximately 200 polders, covering an area of 119,000ha

Tough-going

Low-lying, in the delta of three major rivers, and with more than two-thirds of its workforce engaged in agriculture, Bangladesh is highly vulnerable to the effects of climate change. Flooding, riverbank erosion and saltwater intrusion already make farmers’ lives hard, and heavier rains, fiercer storms and rising sea level are making them tougher still.

“It’s very difficult to get a sense of how powerful the rivers are,” says Guy Jones, Mott MacDonald’s team leader for the recently completed eight-year Blue Gold program. The principal rivers coursing through Bangladesh to the sea are the Ganges, Brahmaputra and Meghna, but there are hundreds of smaller rivers and distributaries. “The scale is huge – Europeans think their major rivers are large, but they are dwarfed by even Bangladesh’s smaller rivers. In flood, when they are about to breach the embankments, they are truly frightening.”

Bangladeshi water engineers have borrowed terminology from another low-lying country, the Netherlands. Parcels of land at or below sea level, known as ‘polders’, have been enclosed and protected by earth embankments, with ditches, drains and sluice gates used to reduce waterlogging. Embankments and drainage infrastructure are regularly washed away when the rivers flood and during storms, destroying people’s crops, homes and communities.

Blue Gold

For most coastal farmers there are few if any alternative livelihoods. To improve their prospects, and with climate change already bringing more intense flooding and storms, the governments of Bangladesh and the Netherlands jointly launched the Blue Gold program in 2013, focusing on polders in the south and south-western coastal areas of the country, where almost 40% of the population lives below the poverty line.

The program was geared to empowering local people in the districts of Patuakhali, Khulna, Satkhira and Barguna to strengthen coastal and river defences protecting their farmland, and to diversify their farming practices. It also addressed scarcity of fresh water for drinking and crop irrigation – a challenge that is also being exacerbated by climate change. Euroconsult Mott MacDonald (part of Mott MacDonald Group) led a consortium of consultants throughout the program, from 2013 to 2021.

Blue Gold has improved crop and water management practices, already giving higher cropping intensities and yields. With better constructed and maintained flood defences, fewer crops and less land will be lost to floods. And in dry seasons fresh water is more equitably distributed. Farmer Field Schools are equipping people with skills in modern farming practices and technologies. And an innovation fund is helping communities improve and take ownership of their livelihoods. The program has already improved incomes for nearly 200,000 households – averaging five people per household, that’s 1M people.

In addition, women’s rights have been strengthened through the consultative, gender-inclusive decision-making and governance practices introduced by the program.

Participatory water management

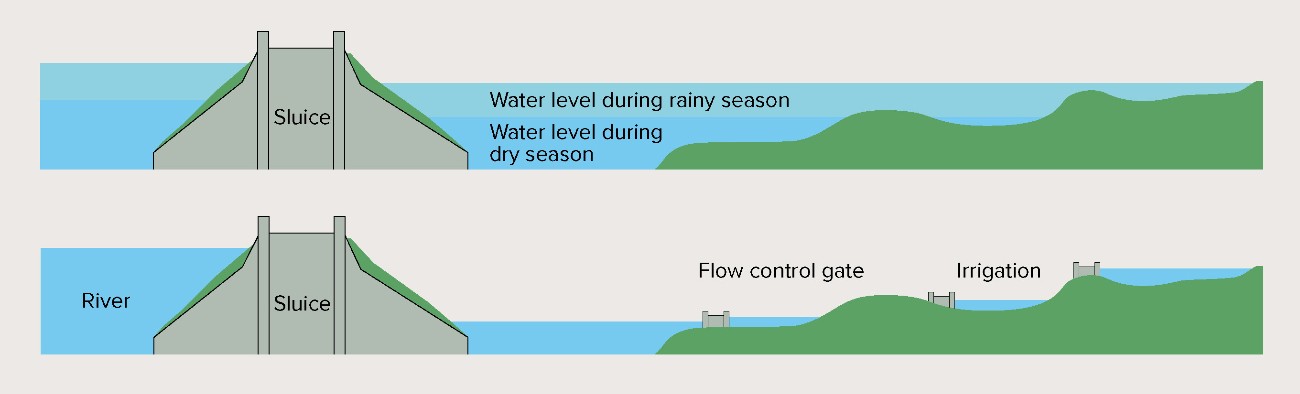

Originally constructed in the 1960s, the polders’ earth embankments are complemented by infrastructure including ditches, canals and sluice gates to drain water from the land, and hold high river waters and tides at bay. Many required rehabilitation.

To encourage communities to participate in the program and invest their time, “we needed to assure people of their safety,” Guy says. “Safety is a prerequisite for people to plan for the future, and we used infrastructure improvements to try to provide that.” Embankments were strengthened to reduce the risk of river and seawater breaches. Silt was excavated from the drainage canals. Sluice gates were serviced and repaired.

Before Blue Gold, damaged and poorly maintained infrastructure meant higher ground lacked irrigation while lower-lying ground was waterlogged (top). Blue Gold provided the improvements to flood defence, drainage and irrigation infrastructure required to improve farming conditions for both higher and lower fields (bottom).

One of the key objectives was to enable polder communities to manage water themselves – keeping flood waters out, draining excess groundwater and sharing fresh water for irrigation equitably. This has been delivered through Water Management Groups (WMGs).

“We had to get people involved,” explains Hero Heering, Mott MacDonald project principal. “We needed to establish a management approach that would work at a very local scale.”

Natok – showing what’s possible

To overcome power imbalances between users of water infrastructure the Blue Gold program used ‘natok’, a popular form of interactive theatre that discusses social issues. To address conflicts of interest, a natok played out the means by which a cohesive and democratic group won out over an influential, self-interested individual. The audience booed, laughed and cheered as the story twisted and turned, ultimately delivering success for the collective. “Natok is an incredibly powerful way of influencing people’s views,” Guy notes.

Every village, every household

Within each polder, WMGs were established for every village, with every household represented. This ensured that local knowledge was tapped, helping identify problems such as silt-laden canals, weak bunds and broken sluice gates, so ensuring money and time would be directed most effectively. It also cultivated engagement and a sense of ownership. “We tried to get people involved from the outset of the planning process,” Guy explains.

WMGs are responsible for caring for the embankments and drainage infrastructure long term. Previously the polders lacked effective means to manage funding and share the costs and responsibilities of operation and maintenance. Now the WMGs in each polder are represented through a Water Management Association (WMA), which also provides polder-wide co-ordination. The WMAs connect WMGs with local government to secure funding for repairs that cannot be managed with locally available labour and resources.

“People have been given confidence: they have a public forum with clear and effective governance to present their needs and objectives within both civic and civil society,” Guy says. “Through the creation of WMGs people can now articulate very clearly, even in front of a hostile audience, the challenges they face and the support they’re seeking. They can communicate a way forward.”

In the program’s eight years, polders achieved improvements in drainage, increased supply of fresh water for irrigation, and reductions in soil salinity – year on year enabling farmers to grow and reap more from their fields.

At a glance

Blue Gold infrastructure improvements at a glance:

-

12.8kmof riverbank protected

-

330kmof embankment reconstructed

-

20.6kmof embankment decommissioned

-

31flow regulators and sluices built or reconstructed

-

181flow regulators and sluices repaired and rehabilitated

-

17new drainage outlets built

-

4new irrigation inlets built

-

225drainage outlets and irrigation inlets repaired and rehabilitated

Increasing and diversifying agricultural production

Socioeconomic as well as land surveys at the beginning of the program showed how precarious farmers’ income was, and how much more so climate change was making it. It also highlighted a contradiction between production and productivity: Farmers were under longstanding pressure to meet production goals for nationally important foods. That resulted in the over-use of land for the same crops, resulting in nutrient depletion and increased prevalence of crop diseases, which adversely affected harvest yields. To encourage cropping intensification and the selection of crops best suited to local growing conditions, the Blue Gold team used Farmer Field Schools.

Farmer Field Schools have existed for many years in Bangladesh, originally focused on helping farmers grow and gather just one crop and a single season. The Blue Gold team expanded the curriculum to cover multiple different crops, spanning all the seasons of the year. Additionally, the schools introduced training in homestead farming skills. “This was one of the first projects where water management was seen as complimentary to agricultural production,” says Hero. The approach was helped because Blue Gold was the first investment project implemented jointly by the Bangladesh Water Development Board and the Department of Agricultural Extension. “This has made a big difference.”

Small investment, big returns

A crucial aspect of Blue Gold was empowering members of the village-based WMGs to undertake smaller rehabilitation works. The program also invested in small flow-regulation structures to control surface and ground water more effectively in their fields. “It was a relatively small investment but the returns have been phenomenal,” says Guy. “It’s allowed two or three crops to grow in areas that had only a single crop previously.”

Working collectively on the drainage and irrigation infrastructure set an example for people to farm more collaboratively. “Linking water management and year-round agricultural production means farmers need to synchronise better – they need to plan and communicate effectively to ensure that everyone’s fields are either effectively drained or receive irrigation when needed,” explains Hero. “If done properly farmers can grow additional crops and that has led to an enormous increase in income.”

Added to those gains are improvements from new crop varieties and soil cultivation methods. But Guy and Hero emphasise that much of the work is simply building on local knowledge and traditional practices. Farmers have been encouraged to experiment with different crops and times of planting and harvesting. It has enabled them to find the most productive uses for their land. Improved crop planning has allowed farmers to better adapt to weather conditions, avoiding heavy rainfall during the early germination stages, which can cause seed to rot in the ground, or cyclonic winds that can knock down ripened crops close to harvest time. Knowledge transfer became a key element of the Farmer Field Schools. Not all farmers could access the courses, but the learnings and practices of those who did attend quickly spread.

“Experiential learning was hugely important,” Guy explains: “We didn’t set out to provide all the answers. Instead we asked questions to help people solve their own problems. There are a lot of people with the same challenges in common, so tackling them and learning together proved very effective. That’s really what the Farmer Field Schools continue to be about – sharing those lessons from experience.”

Bringing together water management and agricultural production

Noresh Mandal is a farmer who grows crops in Polder 30. Previously, his land could only support rice. He struggled with water salinity in the winter and then flooding in the wet season. He and his family were trapped by crop limitation and weather dependency. Their prospects changed with the re-excavation of local canals to create large reservoirs of fresh water. This enabled Noresh to introduce a second crop cycle of watermelon.

Chickens and eggs

Blue Gold encompassed all aspects of homestead farming, including animal husbandry. While studying how a local variety of chickens are reared, the project team introduced hajols. These are hatching bowls made of baked mud, which include two small troughs at the front for grain and water. Hens don’t need to leave their eggs to feed and drink, which means more hatch successfully. Once hatched, hens and chicks are separated; the hen will then lay another batch of eggs. In this way, farmers can get up to six cycles a year from the same hen.

“It’s a simple thing, but it isn’t covered in any books or academic research. More productive chickens… it was one of those things that we learned through experience, and has now become a part of Farmer Field School training,” says Alamgir Chowdhury, Mott MacDonald’s deputy team leader.

From just 10 birds, I can now afford the full cost of my son’s college fees and support my family.

Dipali Mondal learned about hajols from her neighbour, who had been introduced to them at Farmer Field School. Starting with just 10 hens and a cock, Dipali sold 110 hens, 1200 eggs and 300 chicks in her first year. She added Tk49,400 (US$600) – and a regular supply of eggs and meat – to the family pot.

Her status has grown in her family and the wider community. Dipali is hugely excited for the future. “From just 10 birds, I can now afford the full cost of my son’s college fees and support my five family members,” she says. “My dream is to own a big poultry farm one day and I am preparing to make this happen.”

Women’s empowerment

Gender equality is embedded in Bangladesh government policy, but in practice there is work still to do to achieve balance. Women are commonly not recognised as farmers but instead expected to be homekeepers. Women’s access to education, information and resources is more restricted than men’s, in part because they are confined to the domestic sphere from childhood. Consequently men are often viewed as decision-makers, especially on matters such as farming, buying equipment and selling crops. Where women work alongside men, they typically receive lower pay.

The Blue Gold program set out to redress the balance by empowering all polder inhabitants. It set the expectation that women equally as much as men would take greater control over their lives, setting their own agendas, gaining new skills, solving problems and developing self-sufficiency – enabling everyone to improve conditions for themselves and their dependents, regardless of gender.

“The status of women in society has a major impact on the overall status of a community as well as the economic wellbeing of households,” comments Guy. “As a rule of thumb, the more gender-equal a community, the more prosperous it is.”

In the 22 polders covered by Blue Gold, women now have higher status accompanied by better wellbeing and livelihoods, compared to before the program. The benefits have been shared by all, helping to reinforce the case for inclusion and parity. There is still room for improvement, but the signs for the future are encouraging: There are around 500 WMGs. When the program started, the aim was to achieve community representation of 40% women to 60% men. After six years, in 2019, 43% of the membership were women. Women make up nearly a third of executive management.

“Once women understand the importance of good water management for agricultural production, and the impact on family income, they become highly motivated to be involved in water management,” Hero says.

Expanding skillset

Gender inequality was tacked by changing the way Farmer Field Schools worked. The model inherited by the program provided training to married couples, achieving a 50/50 intake of men and women. But wives and husbands were taught separately, pandering to gender stereotypes. Meanwhile, single women or women with husbands working elsewhere were excluded.

Under Blue Gold, the Farmer Field Schools were focused on helping households with the least resources, and in particular landless households. This resulted in much higher engagement of women, who accounted for approximately 88% of participants, acquiring new ‘homestead production’ skills such as poultry and livestock production, vegetable cultivation and fish farming.

The team also held informal meetings – ‘gender courtyard sessions’ – to encourage discussion, exchange of views and understanding, and change the dynamic between men and women. The sessions were initially about encouraging women to join the WMGs, but over time they focused increasingly on women’s role in farming and income generation, and men’s responsibility for sharing domestic work.

Training promoted women’s leadership in the WMGs, and equipped them with the market know-how to network and barter with suppliers and buyers. Providing mobile phones to women allowed them to do market research on pricing from home.

Many of the women surveyed at the close of the program reported that their status at home had improved. Thanks to their part in increased household income, better knowledge and enhanced confidence, and with changing social attitudes, women now have greater power at home and in community life.

Honourable President

In the 2017 the WMG elected 10 women to fill 12 executive council positions. The president, vice president, secretary and joint secretary roles were also all held by women. The women attribute their success to Blue Gold training they had been attending since 2013.

Power shift

Layli’s husband is disabled, and therefore she does almost all of the field work. She sold watermelons to a trader accepting whatever price was offered. After she participated in Blue Gold’s ‘market linkages and women’s empowerment’ training, she gained the confidence to negotiate the deal, having used her phone to check market prices for watermelons.

Paper chain

A €2.45M Blue Gold innovation fund financed more than 40 projects. “It was intended to bring in either proven technologies that had not yet been adopted in the project area, or to introduce appropriate innovations,” explains Guy. “These were not research projects. They were practical, intended to improve lives.”

One example is a project with Khulna University that found a valuable use for water hyacinth, a plant that grows voraciously and can choke drainage ditches and canals. The innovation fund supported development of a process for producing paper from the plant’s stems and fertilizer from its leaves and roots.

The university team set up a pilot program for making water hyacinth paper in one of the polders. Working with members of the local WMG, it showed that the process required no costly equipment and chemicals, paving the way to paper production in many more polders.

We let the communities explain the problems they faced, and invited their ideas about how we could help.

Alongside researching and proving the feasibility of paper production, a market feasibility study was carried out. It showed there was substantial growth potential for products made with water hyacinth paper. It led the university to provide training in how to make items such as wrapping paper, tissues and tissue boxes, notebooks and photo frames.

“We adopted an ‘upside-down’ approach to innovation on Blue Gold,” says Guy. “We let the communities explain the problems they faced, and invited their ideas about how we could help. People within our project team lived and worked in the polders. They listened to the community, and we listened carefully to them, adjusting our focus and investment to their needs.”

Radical, uncomfortable and inspirational

Blue Gold was multidisciplinary in its outlook and approach, bringing together agricultural, engineering and water practitioners to pursue a common goal. For professionals who traditionally work in clear-cut disciplines, “it was radical and quite uncomfortable,” Guy says. “We initially had resistance even from colleagues.”

But the sceptics were quickly won round as the program began to deliver results. “People from many other projects came to see what we were doing and began copying our approach,” says Alamgir. It cleared up any lingering doubts – in fact it was a spur to become more interdisciplinary.”

Blue Gold ended on 31 December 2021. Its final survey and report concluded it had successfully met its overall goal of improving food security and reducing poverty. And the program has been a notable economic success: eight years-worth of investment in training and infrastructure improvement had effectively been paid back in higher productivity and GDP by program close.

However, for Guy “the real success of the project will be determined only 10 or more years from now. We need time to see how many of the ideas sustain and flourish.” And climate change holds an uncertain future. “People have been living in these low-lying polder areas for 50 years and, with well-maintained infrastructure, they now have the best possible chance of continuing to do so for another 50.”

In the delta region of Bangladesh, water is everything. Therefore, at the heart of any long-term change, you will find water management. Improvements in agriculture, the reduction of poverty and the empowerment of women have all stemmed from engineering feats that have created and strengthened polders across the delta. Farming here has become more predictable. It’s less vulnerable and stressful. All family members now work together in the fields. There are more books for the children and fuller plates on the table.Dr Anwar Hossein

Expert in agriculture

Subscribe for exclusive updates

Receive our expert insights on issues that transform business, increase sustainability and improve lives.